Haussmann Architecture: The Other Revolution of Paris

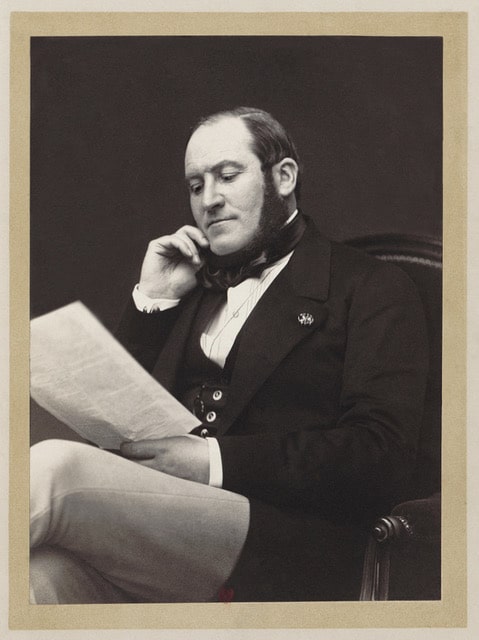

In the middle of the 19th century, the last King of France, Emperor Napoleon III (great-nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte) won the first direct presidential elections ever held in France with an overwhelming 74.2 percent of the votes cast, becoming the first President of France too. One of his first acts was to appoint a somewhat unknown Baron named Georges-Eugène Haussmann, to the post of Prefect for the city of Paris. Baron Haussmann, or Baron to his familiars, was a Parisian civil servant with mild success as the Deputy Prefect in small departments around France. He had no architectural background and yet was put in charge of an ambitious renovation of Paris. And, the result is that the Haussmann style of architecture, revolutionized Paris into the modern age. The style, also known as Haussmannian, is the architecture that defined not only Paris but many of the other large French cities around the nation and in some cases, the world.

Let’s go back in time and think of life in Paris in the 1850s. It was awful, especially for the very poor who lived in the centre of Paris. It was dark, overcrowded and infested with epidemics like cholera and other diseases. There was barely any sanitary water and the sewage systems were non-existant. There could be up to 20 people living in a medieval apartment at one time. The streets were tiny and could barely fit carriages or wagons. It also was rife with strife and an unhappy population that regularly revolted against the emperor, blocking streets and creating riots at their will. This was one of the main reasons why the last Sovereign of France wanted to renew the space, he wanted the poor out of the centre of Paris. And so, the demolition of these medieval neighbourhoods gave way to new parks and squares. The construction of new sewers, fountains and aqueducts, ensuring a healthier, happier Parisian. He went on to remove some 20,000 medieval structures and buildings, while also eliminating the maze-like streets and creating modern grand boulevards. Prior to the renovation, Paris had 12 arrondissements (districts), with 400,000 inhabitants living in an area of 3,300 hectares. Haussmann completely changed all this, tearing up the map and re-dividing Paris into a new grid. Under the Haussmann design, the French capital had 20 arrondissements with 1.6 million residents and covering an area of 10,000 hectares. Part of this was to incorporate outlining towns and neighbourhoods into Paris to increase the tax base, used to pay in part for all of these grande changes.

Haussmann Architecture has a uniformity and an imposing elegance. Each building varies slightly in size and detail but they all have common traits and characteristics. The principles are all based on light, space and movement. They have large stone facades made from limestone with ornamental black wrought iron window grills and balconies. Each roof is made from gray Mansard zinc and is angled at 45 degrees to allow a lot of sunlight. There also was a chimney system that was originally used for heating and now embodies the iconic rooftops of Paris. The buildings rarely exceed six floors and had no elevators, although later in the mid 20th century, many elevators were installed. But the really interesting thing about them was that they were structured to create a small community of social classes. The rez de chaussée, or bottom floor was for boutiques, shops and restaurants. The first floor, sometimes called the mezzanine or entresol, was for storage and store owners. The 2nd floor was for the wealthy and called the Noblesse. These homes were beautifully decorated with French double doors, herringbone hardwood patterns or intricate ceramic patterns, boiseries, elaborate moldings and continuous balconies that you could step out onto for a breath of fresh air. The third and fourth floors had a more conventional style with lower ceilings and standard molding. The fifth floor had lower ceilings also but a continuous balcony to preserve the visual balance with the second-floor balcony. The sixth floor, or attic, was reserved as the maid and servants’ quarters and are the most coveted spaces today, as they feature many desirable architectural features, such as exposed ceiling beams and a rooftop view of the city. Most apartments were painted white to reflect the light. And in some, more residential areas, there were stone paved carriage entrances leading to a central courtyard.

The renovation of Paris happened in three phases. First, the Emperor showed Baron Haussmann the map of Paris and instructed him to “aérer, unifier, et embellir Paris”. In other words, to give it air and open space, to connect and unify it and to make it more beautiful. He also gave the Baron carte blanche on his activities including the expropriation of property by the state, and the Baron would only have to report directly to the emperor. The Baron then set off on his course to change one of the most famous cities in the world. He first created the Grand Cross of Paris, which connects east and west Paris on rue Rivoli and rue Saint Antoine and north-south along two new Boulevards, Strasbourg and Sébastopol. The emperor wanted it completed before the Paris Universal Exposition of 1855, along with a new hotel, the Grand Hôtel du Louvre, the first large luxury hotel in the city, to house the Imperial guests at the Exposition. The first phase was one of the most difficult as it resulted in the displacement of 350,000 poor people from the downtown core of Paris to the suburbs and Belleville. In creating six new huge boulevards, Haussmann’s renovations brought air, light and healthiness as well as easier circulation to the former labyrinth.

The second phase of the project was an even bigger undertaking. He built a network of wide boulevards connecting the interior of Paris with a ring of grand boulevards built by Louis XVIII during the restoration, and to the new railroad stations which Napoleon III considered the real gates of the city. In this plan he constructed 16 miles of new avenues and streets. Haussmann’s plan was grand and made a lot of changes. He completely changed Île de Cité and constructed boulevard Malesherbes, to connect the place de la Madeleine to the new Monceau neighborhood. This construction demolished one of the most sordid and dangerous neighborhoods in the city, called la Petite Pologne, where even Paris policemen rarely ventured at night. He also started working on the new 600-kilometer-long sewer system. It’s still largely in place today, over 140 years later. Haussmann also created several wooded squares and parks around Paris, the two most famous are the Bois de Vincennes and Bois de Boulogne.

Haussmann’s work was met with fierce opposition and he was finally dismissed by Napoleon III in 1870 after 17 years as Prefect. The Baron’s work did live on as his projects continued until 1927. His former Director of Public Works assumed the position upon his dismissal and continued on finishing his grand designs. In the end, along with the items I mentioned earlier, Haussmann also created:

- The construction of two train stations – Gare du Nord and the Gare de l’Est; and the rebuilding of the Gare de Lyon.

- The reconstruction of Les Halles, the large central market, replacing the old market buildings with large glass and iron pavilions, designed by Victor Baltard.

- He also built new markets in the neighborhoods of the Temple, the Marché Saint-Honoré; the Marché de l’Europe in the 8th arrondissement; the Marché Saint-Quentin in the 10th arrondissement; the Marché de Belleville in the 20th; the Marché des Batignolles in the 17th; the Marché Saint-Didier and Marché d’Auteuil in the 16th; the Marché de Necker in the 15th; the Marché de Montrouge in the 14th; the Marché de Place d’Italie in the 13th; the Marché Saint-Maur-Popincourt in the 11th.

- The Paris Opera (now Palais Garnier), begun under Napoleon III and finished in 1875

- Five new theaters; the Châtelet and Théâtre Lyrique on the Place du Châtelet; the Gaîté, Vaudeville and Panorama.

- Five lycées were renovated, and in each of the eighty neighborhoods Haussmann established one municipal school for boys and one for girls, in addition to the large network of schools run by the Catholic church.

- The reconstruction and enlargement of the city’s oldest hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris on the Île-de-la-Cité.

- The completion of the last wing of the Louvre, and the opening up of the Place du Carrousel and the Place du Palais-Royal by the demolition of several old streets.

- The building of the first railroad bridge across the Seine; originally called the Pont Napoleon III, now called simply the Pont National.

His legacy has stood the test of time, and is not too far removed from the Paris we know today. Even now in the sustainable age of the 21st century, there is still a lot we can learn from this icon of French history.

As you may have noticed I’m a huge fan of the Haussmann style and am thrilled that we found one to live in. We are on the 3rd floor of a beautiful Haussmannian building in Montpellier. The ceilings are 12 feet high (4 metres). We have fireplaces in every room of our apartment, although they have been long since disconnected. The apartment itself is huge with 1500 square feet (150m2), filled with moldings and boiseries, along with amazing ceramics and double French doors with Juliette balconies. Interestingly enough, our space is only half of the original apartment. The apartment has the front-facing spaces aka the reception rooms. The former dining room is our bedroom, the music room my office, the main room is still our salon and dining room and the library is my husband’s office. Our neighbouring apartment is the other half of the main apartment and consists of all of the private rooms and bedrooms from the original apartment. The original apartment would have been 3000 square feet or 300m2. It’s been a huge dream of mine to live in such simple elegance.

Like many heritage buildings some of the Haussmann buildings were torn down in the 1970s to make way for contemporary tower blocks. However, the Haussmann legacy continues in Paris, where the remaining 40,000 Haussmann buildings represent 60 percent of the city’s housing stock.

The biggest compliment to the Haussmann-style architecture is that it can be found in all of France’s major cities (Lyon, Dijon Toulouse and Montpellier), as well as in other countries: from the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the United States to Buenos Aires in Argentina.

Vivre ma France,

Receive the news in your emailbox

If you like this articles , you can subscribe to our weekly newsletter.